Shockingly, most of the errors in studies are stemmed from simple misconceptions when defining and distinguishing between the two terms, anxiety and arousal (Ward & Cox, 2004). The proper definition of arousal is an energizing function that is responsible for the harnessing of the body’s resources for intense and vigorous activity (Sage, 1984). Anxiety is properly define as, a negative emotional state with feelings of nervousness, worry and apprehension associated with activation or arousal of the body (Weinberg & Gould 1995). Arousal and anxiety should not be classified together, because arousal is a very physiological state where as anxiety refers to a highly emotional state.

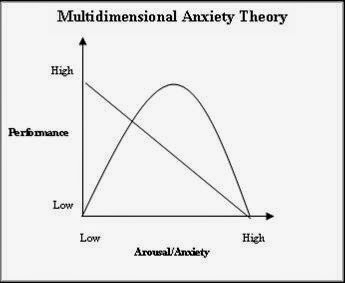

Current research in regards to the how different states of arousal affect sport and performance either agree or disagree with the inverted-U hypothesis but neither has been completely accepted. The inverted- U hypothesis “is the proposition that performance on a task progressively improves with increases in arousal up to an optimum point, beyond which further increases in arousal lead to progressive decrements in performance” (Dictionary of Sport and Exercise Science and Medicine by Churchill Livingstone, 2008). A study done by Neiss in 1988 looked at the downfalls of the theory and suggested it to be faulty due to the fact arousal is such a multifaceted state. In response Anderson (1990) critiqued Neiss’ article and argued in favor of the inverted-U hypothesis saying Neiss’ assumptions were questionable and his references unreliable. Although Anderson (1990) made some valid points he was unable to prove that arousal is not indeed a multifaceted state. In conclusion, the inverted- U hypothesis does give a valuable outline and guideline to follow when predicting the affect arousal has on sport performance however, there must be an awareness and consideration of other influential factors.

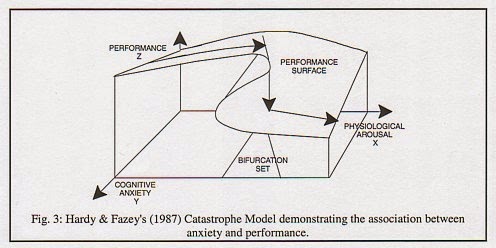

Studies done on the effect of anxiety on sport performance is a little less straight forward then the affect of arousal. The first problem researches come across is separating somatic anxiety and cognitive anxiety because although they are separate they interact (Smith, Smoll, Cumming & Grossbard, 2006). Both the Multidimensional Theory of Anxiety (MTA) and the Catastrophe Model (CM) are common theories often used by researchers (McNally, 2002). They both agree that competitive anxiety is comprised of two distinct parts both having dissimilar effects on performance and the only significant difference between their theories, is the MTA uses somatic anxiety as the asymmetry factor and CM uses physiological arousal (McNally, 2002). Unfortunately, A number of researchers have also drawn attention to the likelihood that cognitive and somatic anxiety are not entirely the independent sub-components they have been treated as, and in fact they actually correlate to some extent with each other (McNally, 2002), which could have detrimental effects on the validity of both the MTA and CM.

Most commonly the graphs presented have all been accepted and followed, however, there is more too this topic then just what these graphs present. Such as a practice-specificity-based explanation which was suggested by Movahedi, Sheikh, Bagherzadeh, Hemayattalab, & Ashayeri (2007), who found positive performance results in athletes who played at the same arousal level in the actually games as they did when they were simply practicing. This is a different aspect of the link of arousal to performance that is not included in the graphs, which leads us to wonder, how do we know there aren't other influential factors being ignored in this topic?

Identification of Critical issues:

References:

Anderson, K. J. (1990). Arousal and the inverted-U hypothesis: A critique of Neiss's 'Reconceptualizing arousal.'. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 96-100. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.96

Arent, S. M., & Landers, D. M. (2003). Arousal, anxiety, and performance: a reexamination of the inverted-U hypothesis. Research Quarterly For Exercise & Sport, 74(4), 436-444.

Inverted-U hypothesis. (n.d.) Dictionary of Sport and Exercise Science and Medicine by Churchill Livingstone. (2008). Retrieved September 15 2014 from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/inverted-U+hypothesis

Jones, G. (1995). More than just a game: Research developments and issues in competitive anxiety in sport. British Journal Of Psychology, 86(4), 449.

McNally, I. M. (2002). Contrasting concepts of competitive state-anxiety in sport: Multidimensional anxiety and catastrophe theories. Athletic Insight: The Online Journal Of Sport Psychology, 4(2), 433-532.

Movahedi, A., Sheikh, M., Bagherzadeh, F., Hemayattalab, R., & Ashayeri, H. (2007). A Practice-Specificity-Based Model of Arousal for Achieving Peak Performance. Journal Of Motor Behavior, 39(6), 457-462.

Neiss, R. (1988). Reconceptualizing arousal: Psychobiological states in motor performance. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 345-366.